Should employees be promoted at random? Science says: “IDK, maybe?”

“In a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence”

– Dr. Laurence J. Peter

The controversial quote above is from a semi-satirical book, by Dr. Peter and Raymond Hull, which since its release triggered quite a bit of research on the topic. The idea behind it is that, as promotions are typically assigned based on someone’s performance in their current role, people rise ranks of hierarchical organizations until they reach a position where they are relatively incompetent and not considered for promotions anymore.

This adverse selection effect can be intuitively expected when performance in a certain role is not a good predictor of performance at a higher role: a stellar programmer is not necessarily a good manager. Or, as Putt’s law states:

“Technology is dominated by two types of people, those who understand what they do not manage and those who manage what they do not understand.”

– Archibald Putt

I originally encountered the Peter principle because I am a big fan of the Ig Nobel prize, and in 2010 three Italians, Pluchino, Rapisarda, and Garofalo, were awarded the Ig Nobel Prize in management science for their computational research on the topic. I always found their result to be very thought-provoking, and since I wanted to try out the Mesa library for agent-based simulations, I could think of no better paper to try to reproduce! :-)

Pluchino-Rapisarda-Garofalo model

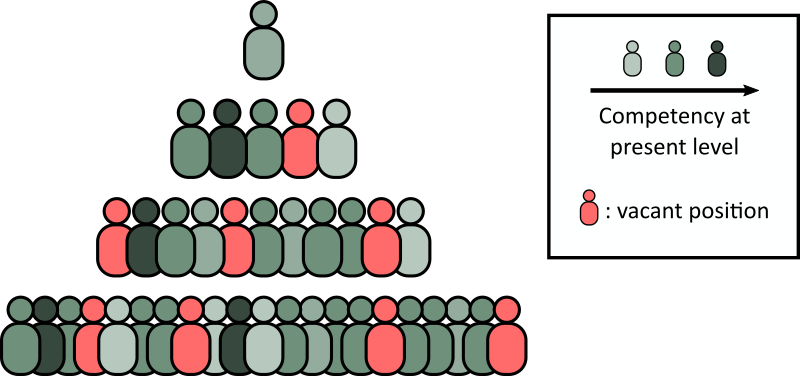

We shall now review the model introduced in “The Peter Principle Revisited: A Computational Study”. Let’s consider a hierarchical organization, where positions are distributed over some number of levels of fixed size; each position can be either vacant or occupied by an employee, who is characterized by two numbers: their age and a score which represents how competent they are in their current role. For the sake of definiteness, let’s assume that the score is a real number from 1 to 10.

The global efficiency of the company is defined as the sum of the competence scores for each employee, weighted by a level-dependent “factor of responsibility” which accounts for the idea that incompetency or unfulfilled roles occurring in the topmost levels are more harmful to the company as a whole with respect to them occurring in the lower levels. The efficiency is then normalized by the score the company would obtain if each employee had a competence score of 10.

Employees can only be promoted to the level immediately above their current one (provided that there are vacant positions in it) and enter the company only at the bottom-most level. How will we model then the competency an employee will show when they’re promoted to a higher level? The authors of this model suggest two possible mechanisms:

- Common sense hypothesis: when an employee is promoted, their competence in their new role is roughly the same they had in their previous role, with some small random variation (say, uniformly distributed between -1 and 1).

- Peter hypothesis: when an employee is promoted, their competence at their new role is completely independent with respect to the one they had at their previous role. Not completely unrealistic, if we imagine someone switching from a role where they need highly technical skills to a more managerial role.

Also, one can imagine a large number of strategies by which we choose an employee to promote at the next level; in the original model, the authors study three of them:

- The Best strategy: for any vacant position, promote the most competent employee from the level immediately below. This is the strategy that is most commonsensical, and “in theory” the one people use in the real world.

- The Worst strategy: rather than picking the best candidate from the level below, pick instead the worst one. Intuitively… WTF?

- The Random strategy: whenever there is a vacant position, write down all the names of the employees that can be promoted to fill it, put them into a fish bowl, and extract one name at random: that guy gets a promotion! Would love to know if anyone uses it in the real world.

Lastly, employees leave the company only if they reach retirement age or if their competence score falls below a certain threshold.

With these rules in mind, let’s implement an agent-based simulation to see how a company, with random initial ages and competencies of employees at the start, evolves over time. If you are not interested in the details of the implementation, feel free to skip to the discussion of the original results section.

Implementing the PRG model with Python

As this is a very simple agent-based simulation, I think a natural choice for its implementation is the Mesa library, as it allows us not to write a lot of boilerplate code for our simulation while at the same time being much more easy to use with respect to some more sophisticated library (e.g., SimPy). The goal of this section is just to sketch how does the implementation of a simulation like this looks like; for more details, feel free to take a look at the full repo for this post and at the Mesa docs.

We can start by writing a fairly uninteresting Employee class as

follows:

The Employee.step() method describes what agents do at each time step of the

simulation; in this model, it is very simple: they just get older and approach

retirement age.

The model describing the company dynamics is slightly more involved; here I am reporting only the methods which are most important for this model:

As you can see, the strategies we described above for promoting employees and recalculating competencies are essentially one-liners.

Mesa models have a very useful attribute, data_collector, which can keep track

of whatever observable we want during our simulations, and give us back a convenient pandas.DataFrame.

We can make use of that, and simulate the dynamics of a company via the following:

I.e., we just need to repeatedly call the model.step() method, and all the rest

is more or less taken care of automagically. For running batches of simulations,

one could also have used Mesa’s

BatchRunner class.

Without further ado then, let’s look at the output of my implementation of the Pluchino-Rapisarda-Garofalo model.

Discussion of the original results

By simulating the efficiency over time of a batch of companies, under the assumption of either the common sense hypothesis or the Peter hypothesis, and assuming they always promote either The Best, The Worst, or The Random employee, we get the following plots:

Here, each line shows the average from 50 simulations runs. The companies were all identical: initially filled with 160 employees, distributed among 6 levels of size 1, 5, 11, 21, 41, and 81. The weight of each level on company performance was of 1, 0.9, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2 respectively. The age of each employee was randomly initialized from a normal distribution centered at 25 years with standard deviation of 5 years, truncated to have support from 18 to 60 years, whereas the competence score was randomly sampled from a normal distribution centered at 7, with standard deviation of 2, truncated to have support from 1 to 10. Retirement age is set to 65 years.

As one can imagine, when the common sense hypothesis is valid, i.e., when competence in the new role of an employee is fairly similar to their competence in their old role, between the strategies we introduced above the better one is to fill vacancies by promoting the best employee, whereas always promoting the worst one on average leads to a decrease in efficiency, and promoting at random sits between these two strategies.

These trends are completely reversed under Peter’s hypothesis: always promoting the best employee leads to a decrease in efficiency. Intuitively, we can explain this phenomenon as follows: by promoting the best employee to fill a position, we are getting rid of the best performer in a level; at the same time, as the new competency score is completely random, the employee’s competency at their new role (which will have a higher impact) will very likely be strictly smaller. We are dealing with a textbook case of adverse selection here! By promoting instead the worst performing employee of a level, we are both replacing them with another employee with likely higher competency, and we also get the chance to re-roll the die for their skill at a new level (which will also likely be higher than before).

Now one question should would be quite natural: in a real organization, for a given promotion, which competency transfer mechanism is at play? In the scenario where common-sense hypothesis and the Peter hypothesis are equally likely, Pluchino, Rapisarda, and Garofalo have shown in their paper that a relatively efficient strategy would be to promote, at random, either the best or the worst candidate for an open position!

Extensions of the model

Another odd thing to notice in our results is that the dynamics are quite unlike what one could expect: nothing much happens for about 25 years, and then in a matter of decades we reach equilibrium. This has to do with the fact that positions are initially entirely filled, and since for the chosen age distribution 99.85% of the employees are under 40 at the start of the simulation, we will need to wait quite some decades to start seeing anyone retiring.

This artifact can be easily fixed by assuming that at the beginning some positions are unfilled; this can be done by imposing that the number of agents initially at each level is not given by the level size, but rather from a binomial distribution (see this line in my implementation), such that there is always a random chance that a position is vacant. I decided to use the same probability of vacancies for each level, but decided to have always at least one person per level (see here). For the sake of definiteness, let’s pick 0.2 as the probability for each position to be initially vacant.

Also, I introduced some random chance that people leave the company at any given time before retirement (maybe they got a better offer from a company which does not host lotteries for promotions :-P). Let’s assign to each employee a 4% chance to leave the company every month, so that on average each employee stays about two years before leaving their role.

As the kind of businesses I am most interested in are early-stage startups, I also decided to consider companies less stratified and a bit smaller with respect to the original paper. Therefore, let’s consider a company with one CEO, a board of five people just below her, ten “managers” of some sort, and thirty people below them. I set the weighting factors to 1.0, 0.8, 0.5, and 0.2 for each level quite arbitrarily.

Finally, let’s use a simulation step of one month rather than one year, and run this new simulation for batches of 256 companies for each combination of promotion strategies and competence transfer mechanisms. The results are shown below:

We can see that now the dynamics is more gradual and happens on a more meaningful timescale (years instead of decades/centuries). Apart from this, nothing much seems to have changed from the original model; the gaps between the strategies appear to be smaller in this case, but I think is due to the different company structures I used, instead of any difference in the model. The main point still remains: contrarily to common sense, promoting the best employee under the Peter hypothesis leads to a decrease in efficiency.

Questions left as an exercise for the reader

The modifications of the original model I proposed above are just some small fixes, and it would be interesting to see how the results would change in case we relax some assumptions. My suggestions on the way forward would be, for instance:

- Employees can only enter at the bottom of the hierarchy; what about including in the model the possibility for a company to hire experienced people from outside the company?

- The competence score distribution, under the Peter hypothesis, was the same for all levels. Would it be meaningful to differentiate it depending on the level?

- Employees are very one-dimensional in this model (their effect on the company is characterized only by one number). Can we make them, if not as complex as real humans, at least slightly more interesting?

- Are there any other interesting competence transfer mechanisms to consider? For instance, some freshly promoted individual might not be as effective as their peers, but they could be coached by (some) people in the same level, so that we have at least some regression to the average.

- Here I studied only average quantities; what about distributions? Is the risk associated with each scenario comparable?

- Can we model the effect of discrimination, by providing each agent with a “gender”, “race”, or similar attribute?

Conclusion

How much models like the ones we have been looking so far actually model a company is still, in my humble opinion, very questionable. For instance, it is extremely unlikely that competence is the only (or even the most important) thing that a company typically considers when deciding to hire or promote someone; the objective-looking metrics usually justifying this kind of decision are often only a façade for biases and discrimination. Typically, the more metrics, the less transparency is there. Paradoxically, could we ameliorate the problem of discrimination in the workplace by randomizing hiring and promoting employees? Of course, I am not saying it could be the best solution, but would it improve on the current status quo?

I think we still understand very little about what really motivates people, and how hierarchies really work; still, agent-based approaches can often be a good inspirations for further research. Also, they are relatively easy to code (especially by using some dedicated library for them), as one just needs to provide the simple rules which govern agents behaviour. I can wholeheartedly suggest the Mesa introductory tutorial, where they implement another interesting model (the Boltzmann wealth model), for more on the topic.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading!